See part I here.

I’ve been thinking about isomorphisms a lot (because it’s one of my favorite topics) and this blog is chock full of my isomorphisms that I use to understand social interactions coupled with human body limitations. And I was wondering if creating multiple isomorphic examples for a complicated concept might make it more accessible to people or even introduce further understanding for people who connected to the first pass at the subject.

All this to say, we’re going to take this post to look at the same comics from part I and discuss them in terms of a timer or alarm and see what happens.

Sidenote: Isomorphisms are different things that are structurally similar that you can look at multiple ways to learn about both the first thing you are looking at and the other thing you are comparing it to. Metaphors are isomorphisms. Visual charts are isomorphic to the data they represent.

Why a timer?

I think it’s fair to say that everyone who’s reading this blog post from an internet connection has used a timer of some sort.

We’ve all had the experience of using a timer in tons of different ways: a morning alarm clock, a school bell, your phone rattling loudly on vibrate, the buzzer on your oven, the electric coffee pot beep, the flashing light of a fire alarm, the app on your TV asking if you’re still really watching yet another tv show.

And we’ve all experience not being able to notice a timer when it went off. More importantly, we’ve experienced the consequences that can arise from not receiving the message.

The timer analogy also makes it easy to show how you can completely miss even the fact that you’ve missed the signal and to misinterpret the reason for why you missed it. When I started losing my hearing, I was convinced my tea pot was becoming faulty because I couldn’t hear the whistling when I was upstairs and nearly burned down my house several times because I boiled the pot down to nothing. Not only was missing the signal causing potential harm, but I had to (eventually) understand and take measures to fix my ability to literally hear signals, and, in the meantime I had to create new means of signaling to be able to correctly receive signals. Signal adjustment and reinterpretation is the logical output of signal detection theory…but let’s not get ahead of ourself.

Fun note: If you extend this metaphor for social situations, then I can either be the oblivious person upstairs missing signals or the tea pot downstairs giving off signals that are never received. I quite like imagining myself to be a grumpy teapot.

Now, back to the timer

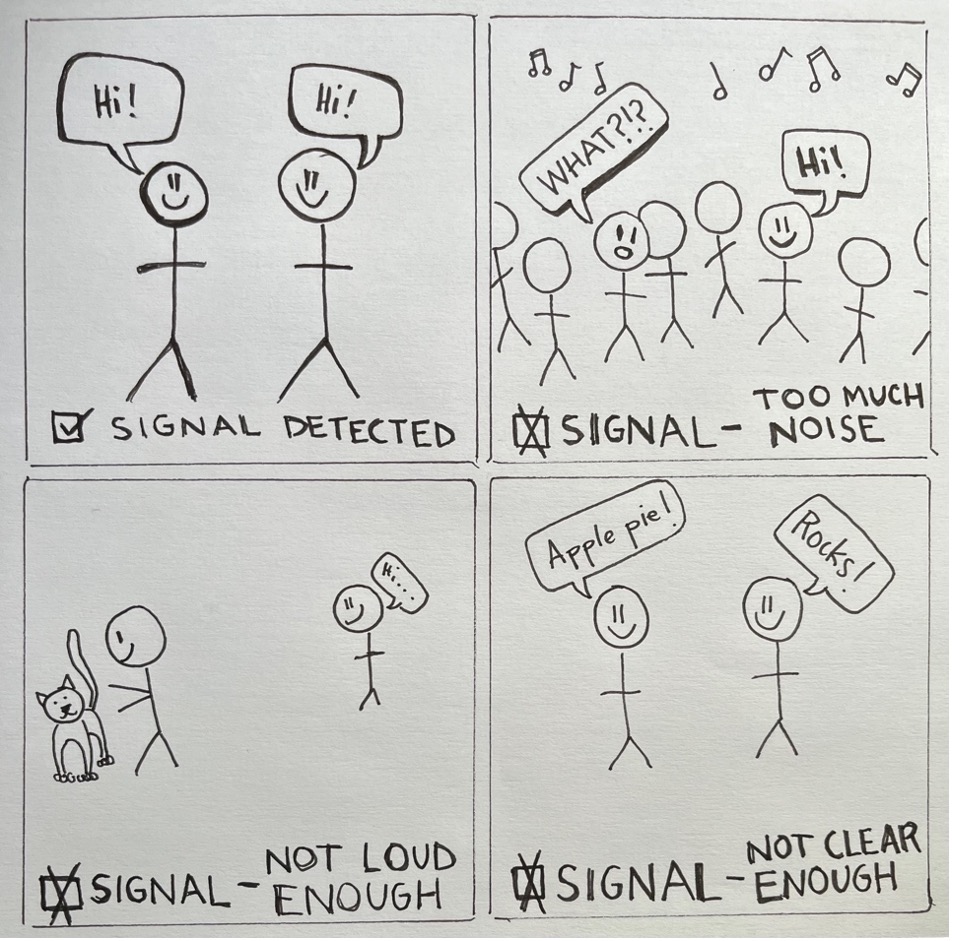

There are a lot of things that go into the strength of a social signal. We’ll use these beautiful stick figure drawings to compare how this might look in the four different scenarios from the previous post.

Successful timer

In the top-left panel, we see two people saying “hi” to each other in a way where both can understand and notice the social behavior of the other.

If this scenario were a timer, this is when the timer works as intended. It sends the signal, you correctly receive and interpret the signal, and then you initiate or conclude whatever action the timer was supposed to indicate.

Too much noise timer

In the top-right panel, we see two people at a large gathering trying and failing to understand each other’s social behaviors because there is too much “noise”.

Noise in signal detection theory can include actual noise, but is can also mean that there is just too much data incoming and it is drowning out the signal. You can think of this like a timer that is in a whole room of timers where they are all going off. How do you know which timer is yours? Or if your timer is going off when you’re outside next to loud traffic, how can you hear it? What about if you’re running with your phone in your pocket when the alarm vibrates your phone?

Socially this could look like someone who socializes a lot not noticing a person has made an effort to befriend them because they already have a lot of social activities occurring at all times.

Weak timer

The bottom-left example shows someone not noticing another person trying to socialize with them because something else has their attention (in this case, a cat).

Imagine your timer ends with a bright flashing light to get your notice. This would be very noticeable if it was an alarm that woke you up in a dark room. However, if the same alarm went off when you were outside in the sunshine, it would not be as noticeable. You may only notice it if you are looking directly at it.

In socializing this could look like people not being clear enough about their ask or intention for people to recognize the signal is occurring. This is especially true when people rely on subtext or symbolism to convey their intention (e.g., “I mentioned a TV show based on the King Arthur story, it was obvious I wanted to be invited to the Renaissance Faire”).

Unclear timer

The bottom-right panel shows what happens when the signal is unclear or misinterpreted.

If every time your timer concluded its cycle something novel and weird happened, like a potato appeared on your counter the first time, second, your faucet turned on, and third, a bird chirped…you’d never be able to act on your timer because you’d never understand when the timer went off.

The same can be true with social signals. In the cartoon, both people are making bids for socialization, but the bids aren’t being made in a way that they other person understands it (it is hard to find immediate common ground between baking and geology).

Did the timer help?

I think it did.